Thirty years ago, American evangelicals were mailing $50 donations to organizations that liberated enslaved Christian in Sudan from their Muslim captors. Evangelicals flew halfway around the world to see women and children receive their freedom in real time. They advocated for US foreign policy that hit religious freedom violators with sanctions. Those penalties hit Sudan in 1999, the year after Washington established the Office of Religious Freedom. American evangelicals cheered on a peace agreement that ultimately allowed Sudan’s majority-Christian population to separate and form the new nation of South Sudan. Their investment even prompted them to speak out in 2004 when violence broke out in Darfur, a majority-Muslim part of Sudan.

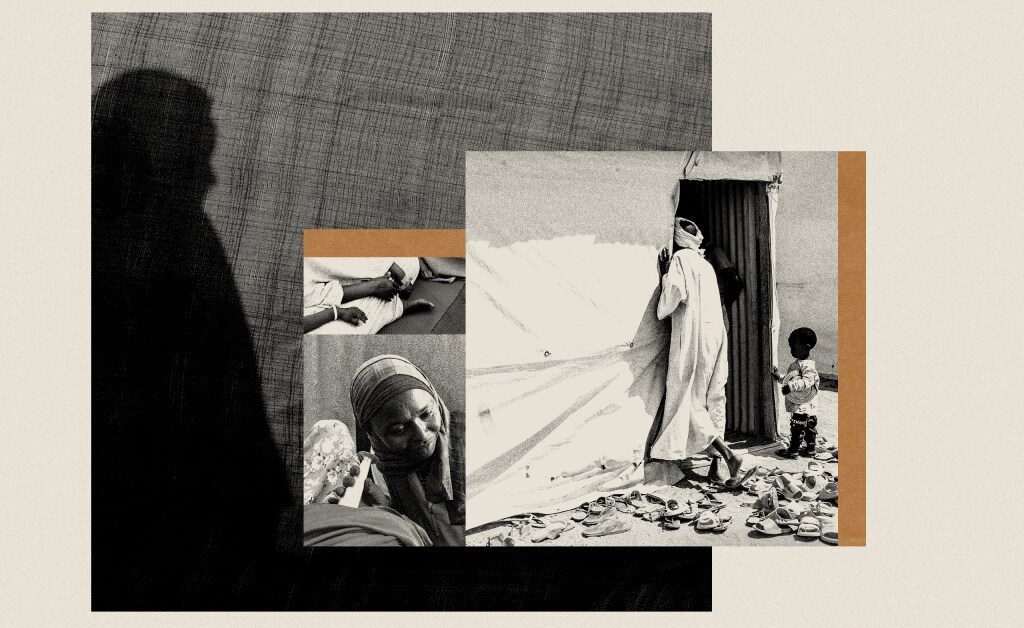

Two decades later, Sudan’s civil war has once again created an enormous humanitarian crisis.

The once “straightforward” narrative of genocide has been complicated by a political reality where the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces (RSF), former political allies that collectively overthrew a dictator, now wage war against each other. Observers accuse both of murdering thousands of men, raping women, and displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

But this time, American evangelicals have yet to personally connect with the Sudanese plight. The perpetrators are Muslim, as are most of their victims and the residents in the region of Chad where many have fled. Chad’s larger Christian denominations have failed to organize large-scale relief projects or evangelistic initiatives for refugees. Their absence reduces the profile of local church efforts, said a local missionary.

Even though World Vision and Samaritan’s Purse—two groups American evangelicals regularly support—have provided humanitarian aid to fleeing Sudanese, their efforts come at a time when ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza have captured significant Western attention and money. Even US taxpayer money that had funded initiatives for Sudanese refugees is likely a victim of the Trump administration’s USAID demolition.

Two years into a conflict that has killed at least 20,000 and forced 12.5 million—approximately the population of Illinois—out of their homeland, the existence of the crisis, much less its specifics, hasn’t reached the radar of most American evangelicals. I recently traveled to Chad to see what life is like for the 200,000 refugees at a settlement in a border town of Adré and at a camp of 56,000 in Farchana, 20 miles west.

World Vision

World VisionWith the world’s attention elsewhere, Entisr must pick up the pieces of her life by herself. (Christianity Today is using a pseudonym for her because she is a sexual assault victim.) Before she crossed the Chadian border, the 27-year-old from Darfur had already been displaced five times. But she still had plans. She was studying public health.

Now she’s sleeping on the ground sheltered by a couple pieces of tarp, along with more than 700,000 others in Adré, a city of 40,000 people along the Chad border, where people kick up dust clouds as they travel back and forth on foot, donkey, horse, or the occasional motor vehicle. Given Adré’s proximity to the border, the government is nervous about the war spreading into Chad, so it won’t turn the spontaneous settlement into an official refugee camp, meaning that Entisr’s three children don’t have any school options.

Instead, she has too much time. Time to worry about her children’s education and time to think about the degree she wanted. Time to miss her husband, whom she hasn’t heard from since June 2023. Time to relive her husband’s coworker imprisoning her for two days so that he and other RSF soldiers could take turns raping her. Time to cry for hours and wish her mom was still alive to comfort her. Time to ponder the future.

“Tell the American people to push for peace and stop the war,” she says. “The majority of victims are women and children. We’ve had enough. We shouldn’t experience this.”

Entisr hasn’t told her family about what the RSF did to her. But she has begun bringing women together to talk about the trauma they endured. These meetings have also turned into savings circles, where women pool money they earn each month to buy materials for handicrafts. The camaraderie has propelled her to share her story as a way to support her fellow survivors.

World Vision

World VisionKhadija Mohamed Adam, a croc-wearing 38-year-old Sudanese midwife, fled with her family to neighboring Chad during the height of the early-2000s Darfur crisis. Each week, she and her teammates at Farchana Camp Health Center deliver an average of 30 babies, the children of refugees like her and of those who fled the country when Sudan’s latest civil war began.

Some of those children now chase each other around the Farchana camp wearing T-shirts with TikTok logos their families bought at the market. Others lie lethargically alongside their moms on beds in the clinic’s malnutrition center, their wasting frames desperate for the supplements they’ve received to kick in.

Daytime temperatures often rise above 100 degrees in the camp. Women in hijabs with wrist-length sleeves and ankle-length skirts doze under a shaded shelter in the middle of the clinic campus.

Adam could use that type of break. On the day I visit, her team has delivered three babies by mid-afternoon. In the next hour, two midwives escort a woman inside a birthing room, and within minutes, the wails of a newborn puncture the courtyard air.

Adding to Adam’s workload are the effects of faraway policies: Canceled USAID grants forced the clinic to fire more than half its staff, including 6 of the 14 women on the maternity team. Adam, a mother of four, now works two extra hours each day to pick up the slack.

“We will not say we are happy,” Adam says, her feet dangling off a bench outside the maternity ward. “We just pray the situation will be changed.”

World Vision

World VisionHatim Abdallah al-Fadl, an English-speaking former UN administrator and translator with a master’s degree in peace and development, has helped catalyze change. When he arrived in Farchana a year ago, he found only three water distribution points in his section of the camp. There were no schools in the area either, even though the camp could have received funding to establish them.

This was unacceptable, Fadl thought. He invited people to a meeting where he asked everyone to share their professions and areas of expertise. Then, he set up health, engineering, and agriculture committees. He formed a group for women’s activists and organized religious leaders into a wisdom council to advise on social problems.

Fadl helped the water committee contact external organizations to inform them that the camp had technicians and engineers living onsite—they just needed tools and infrastructure to build more water-distribution points. A German nonprofit helped the teams to extend several pipelines, and by January, the camp had 20 water taps.

“Twenty instead of three,” says Fadl. “But still we are asking for more.” He also hopes that they will be able to drill boreholes so they can stop relying on the town’s water supply.

As he stands several feet away from a group of children who are giggling loudly while copying the dance moves of World Vision staff members, Fadl feels a sense of satisfaction to see the kids in school. After tracking down teachers, Fadl asked them to start instructing students in the shade of leafy trees. Different charities began donating blackboards and tents. In less than a year, this part of the camp had launched three primary schools, serving hundreds of students each.

World Vision

World VisionLike many of the recent refugees forced from Darfur since 2023, Abdulrashid al-Mohammed is still dealing with trauma. The RSF burned down his home in Al Junaynah, a city in West Darfur, and killed 11 of his neighbors.

He’s haunted by the voices of the wounded and dying villagers calling out for water when he and his family fled, a journey that took them three days. He couldn’t stop—not with his wife and four children—but he can’t bear that he didn’t. Even though he has changed his phone number, RSF members still spam him with video footage of gunmen shooting people and homes burning down.

And yet he’s building a life in Farchana. As he stands in the center of his primary school campus on a sunny Sunday morning, students scurry around with heaping trays of rice, flavored with pinto beans, salt, and oil that comes from a can boasting an American flag and the USAID logo. Behind him lie seven tent classrooms arranged in a U. In front of him sits the former prayer room that now serves as a storage closet, while just outside the school, a cluster of women hunch over giant vats, stirring the day’s meal over open flames.

Mohammed has served as the refugee school’s headmaster since it opened last year. The tent classrooms overflow with more than 100 students.

With classes in full swing, Mohammed has a list of ways he wants to improve the school. He needs at least one other French teacher so students can learn Chad’s other official language. He doesn’t understand why progress has slowed on building brick classrooms (“Other schools have bricks”), which keep everyone dry when the rainy season hits.

He’s still in awe that the school now serves lunch, an initiative that keeps students on campus during the school day and feeds entire families, as kids balance plates of rice on their heads and carry their leftovers home. But the school doesn’t have onsite access to water, which makes sanitizing utensils and pots time-consuming. He’s also frustrated with how quickly open-flame stoves lose heat. He wants his cooks to use gas.

Mohammed is now losing sleep over a new problem. In January, when the Trump administration dismantled USAID, it slashed funding to a secondary school program that served 256 young adults, ages 15 to 25. He says some disillusioned students have already ditched the camp to return to Sudan, where the RSF has subsequently kidnapped and conscripted them. The former teacher loves seeing children learn how to read and believes learning offers his students a life beyond the camp. He blames the war on a lack of education.

Young people tell him they’d rather enter Libya and board boats to cross the Mediterranean “because there’s nothing for us here.” If the secondary education program stays closed, “it will be like we did nothing,” he says.

USAID cuts have also affected the Farchana camp’s relationship with the Chadian residents in the adjacent city. Because the two groups share water and food for their livestock, the influx of refugees has overwhelmed the community of 128,000.

In recent months, an increasing number of locals have visited the clinic, which also offers vaccines and primary care “We are a medical center, but we function like a hospital,” says Albachir Mahamat Albachir, the director and doctor.

At the end of February, Albachir planned to celebrate that the clinic now had consistent access to running water and electricity under a World Vision initiative. For months, they had to charge expectant mothers for water.

But since losing 70 percent of its funding due to USAID cuts, the milestone feels bittersweet. They no longer offer vaccines. With other service reductions, Albachir says some patients will die because it will take too long to drive the sickest people in the clinic’s sole ambulance 20 miles over sandy and rocky roads to the nearest medical provider.

If the money doesn’t come, they may have to close.